Human-robot teaming is stymied by the ultimate hardware incompatibility issue. Humans reason and make decisions using their brains, an awesome and not fully understood supercomputer, honed through millennia of evolution. Robots mostly use math. These hugely different reasoning styles lead humans and robots to reach different solutions and conclusions. In the visual below, the robot will pursue the true optimal - the lowest possible value for the cost function visible. Humans will reach a low value, though it is unlikely their solution will be optimal. It will instead be satisficable - or “good enough”. This is because human brains are built to solve real-life problems, where the optimal solution may not exist, or it may not be computationally tractable to find it fast enough.

This hardware difference makes it very hard for us as humans to collaborate with robots. When humans collaborate, we build what is called a mental model of our teammates – a structure that we use to predict and estimate the behavior of others. This helps us to set expectations about what someone’s capabilities are, or what they might do. Unfortunately, while the mental models we build are amazing when applied to other humans, they’re pretty bad when we have to reason about robots. Robots don’t match our expectations, and we find them very unpredictable. Anyone who has watched something like a robot vacuum do its work knows this to be true. Oftentimes, the robot will do something that confuses, or irritates us, because it has a different set of sensors than we do, and is using math to reason over that information.

But we want robots to be predictable, because more predictable teammates lead to better collaboration, and we prefer to work with predictable robots. When the robot is more predictable, there are a lots of downstream benefits, such as increased trust. So if we can alter the robot’s behavior to be more predictable to humans, there’s a lot of benefits to be gained, both in performance, but also in how people feel about working with robots.

Unfortunately, getting humans to change their behavior is hard. Changing the robot’s behavior is a lot easier, because we program them ourselves. So in this work, we focus on altering robot behavior to be more in line with human expectations. So what do humans like? A lot of research tells us that humans LOVE patterns. Pattern recognition, extension, and abstraction are critical aspects of our intelligence, and we are able to do them as toddlers. So if we base the robot’s behavior on patterns, humans should be able to recognize what the robot is doing, and our brains should be pretty good at continuing the pattern, as well as abstracting it into new environments.

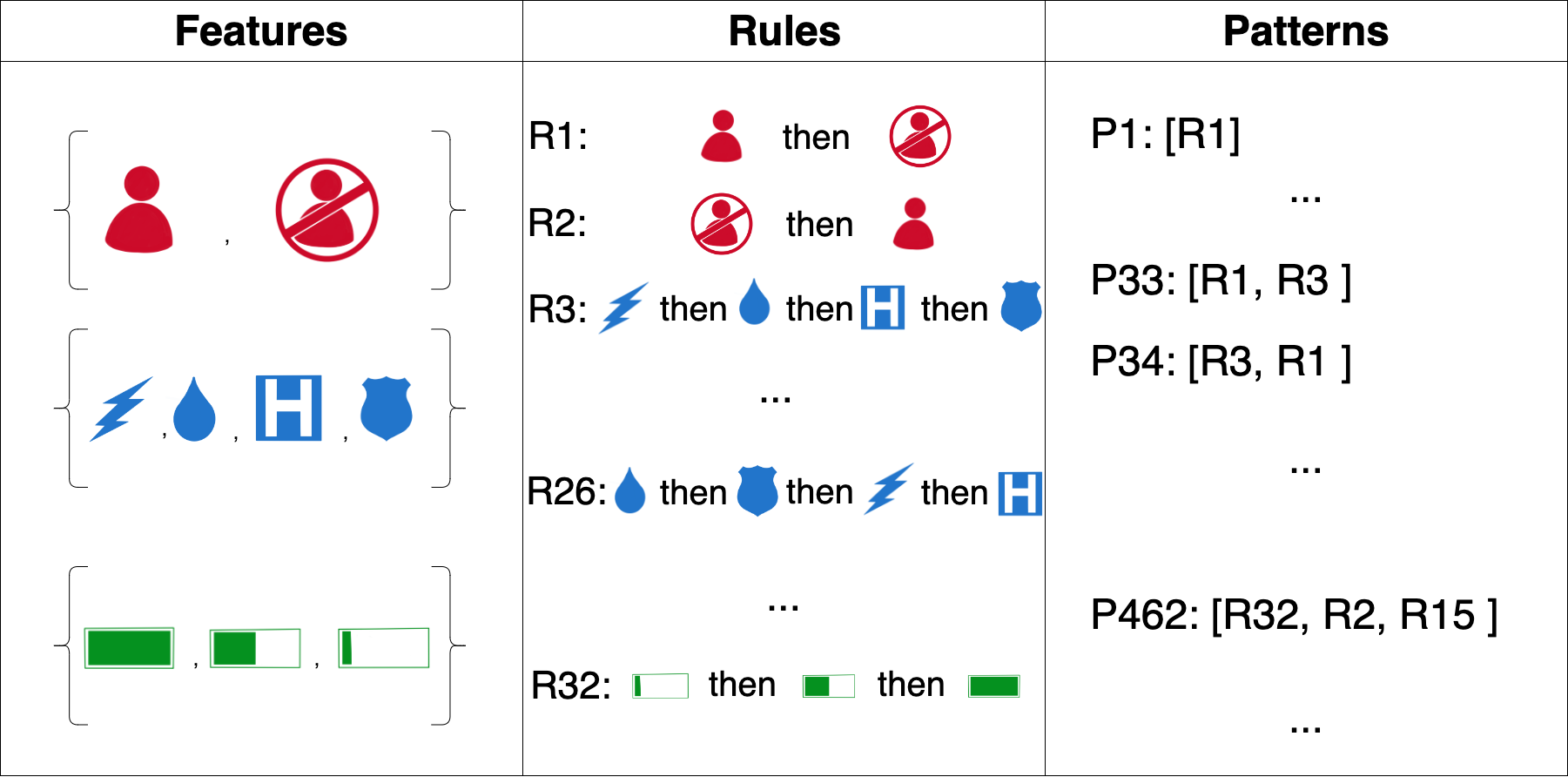

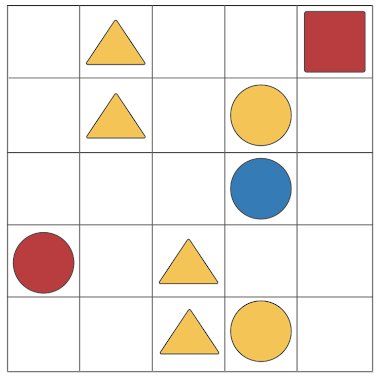

We’ll structure this as a subtask planning problem, where the robot will complete a set of subtasks (like fetching a certain item, or etc) in a particular order. We’ll set up our environment such that there’s an optimal way for the robot to behave, so we can compare it to our method. We need to make sure that humans will be able to see the pattern, so we’ll build our patterns based on features of each subtask that they can see. An example setting is shown below. The robot will have to navigate to all of these locations. The locations have several features each, which we will use to construct our patterns.

We will ignore optimality for now (stay tuned for our current work that seeks to balance optimality and predictability more explicitly!). We want the pattern to be easy to follow, such that if the human knows the pattern, what subtask the robot will complete next is obvious (ie there’s only one subtask that fits the next step), so we want our patterns to be as deterministic as possible. Because humans are so prone to pattern recognition, they might see a pattern in the robot’s behavior that doesn’t actually exist. So we want to ensure that the robot’s behavior can’t be explained by a bunch of different patterns, so the pattern should be unique. This means that only the pattern the robot is following can fully explain its behavior – there’s no ambiguity about what pattern the robot is following.

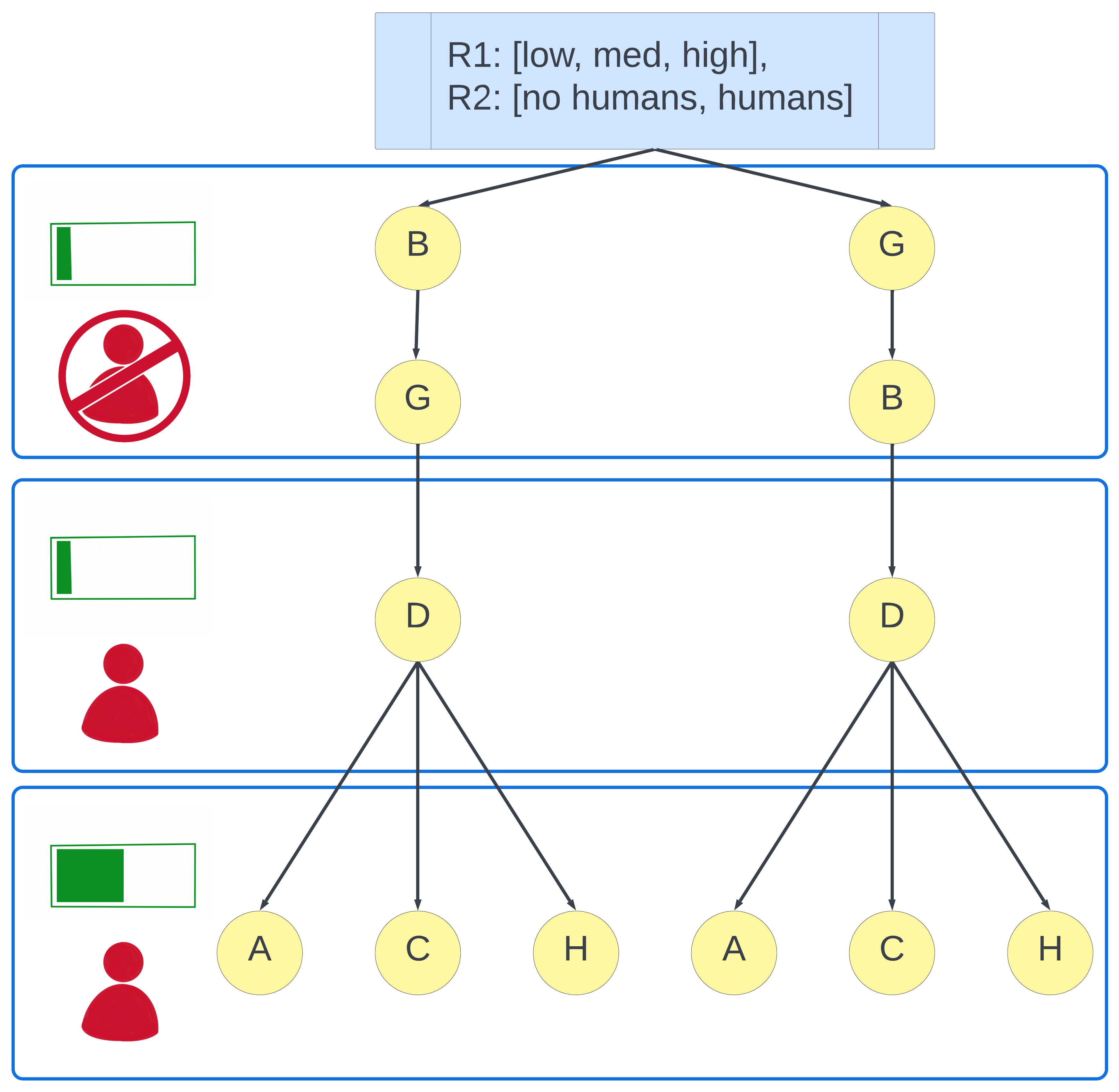

To select the right pattern, first we build a gigantic pattern bank that contains every possible pattern given the features of the subtasks. Then using each of the patterns, we’ll construct a pattern tree, which contains every possible order of subtasks that follows the given pattern. This way, we can easily determine if the pattern is good or not, because we can see every possible way the robot could use it.

Then we have to score each pattern, using these trees.

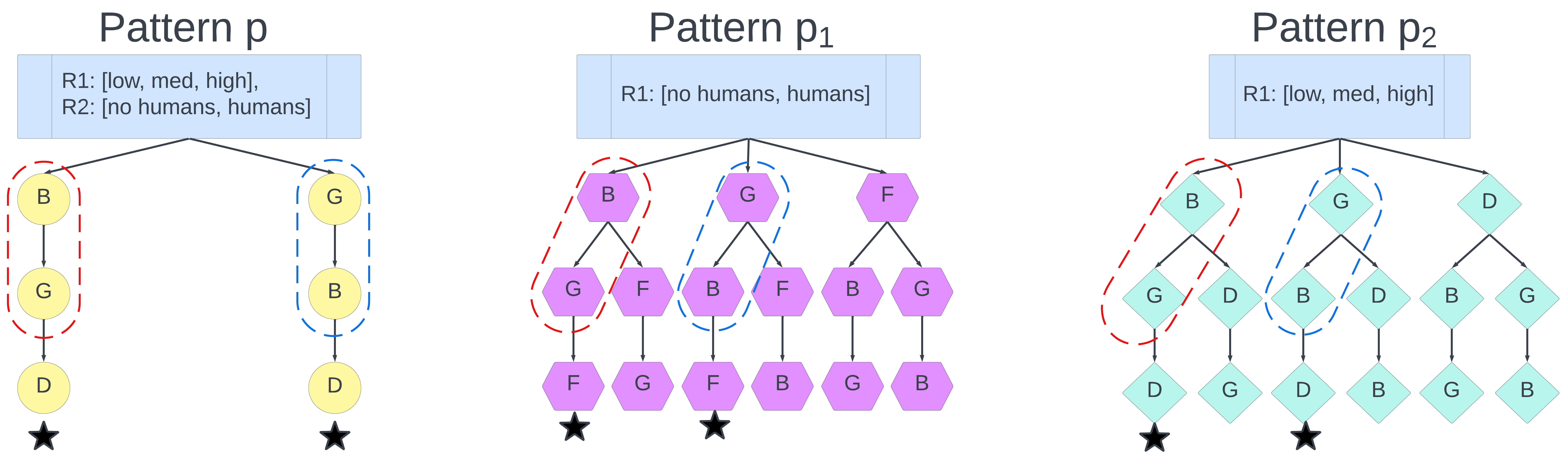

There’s some math, which we won’t show or get into too much here. For each subtask the robot picks, first we ask: given the pattern, what could come next? Then we calculate the entropy over the group of subtasks that might come next. We want a low number here; as a lower value indicates there is little new information added by picking the next subtask. Next we ask: are there any other patterns that match the robot’s behavior thus far? If so, we want to see what the possible next subtasks are for those patterns, because a human might think that the robot is doing that pattern. The picture below shows this process across three pattern trees. We will then calculate the entropy over the group of next possible actions for the real pattern as well as the matching ones. We’ll multiply that number by the proportion of matching patterns in the whole pattern bank. Because if there’s a million possible patterns, and there’s only one matching, that’s a lot better than if there’s only ten patterns in the bank and the pattern we’re scoring matches five of them.

We’ll add those two numbers together, scaling the second one by how many patterns in the pattern bank could explain the robot’s behavior so far. We’ll then do this calculation for each action the robot will take. When we have scores for all the patterns, we’ll pick the best one. We call this method PACT (Pattern-Aware Conventions for Teaming).

Of course, we have to test this with real people to see that it works. We constructed a human-robot coordination game to test the teams’ ability to coordinate their actions. In this game, a grid is placed between the robot and human, and nine blocks are placed in various squares of the grid. Each block has a colorful shape on it, which is visible to the human, and has a numerical value, which is only visible to the robot. Teams will attempt to coordinate on which block they should remove from the grid next. Both the robot and the human will secretly select a type of block to remove from the board. When they’ve both made a decision, each player’s selection will be revealed to the team. If they coordinate successfully, by choosing the same block, they’ll get a reward, and the robot will be able to remove the block from the grid. If they picked different blocks, a penalty will be assessed, and they’ll have to try again. The score is based on the numerical value of the block that only the robot can see. This way, there’s a certain sequence that will maximize the team’s score, if they can coordinate. The score decreases as time goes on, because the fewer blocks there are, the more likely it is that guessing randomly will work, and we don’t want to reward that. The teams played three rounds, and the robot’s strategy for picking blocks stayed the same the entire time, so people could learn to coordinate better by the end.

We divided participants into three groups. In the first group, the robot would select blocks optimally, such that in perfect coordination, the team’s score would be as high as possible. We had two experimental groups, because we wanted to ensure that any success would not just be due to using patterns, but due to the PACT method of selecting the best pattern. In one group, which we called our Median Group, the robot’s behavior followed a pattern, but a pattern was selected such that its score was close to the median score for all patterns in the pattern bank. So a pattern, but not the best one. These patterns were usually deterministic, but not often unique. The third group saw the best pattern as determined by PACT. In the pattern groups, the robot would follow the same pattern across all three rounds.

We collected all sorts of data, including game scores, decision making time, number of mistakes, as well as a ton of survey data. We also interviewed participants after the surveys were done, to see what they had to say.

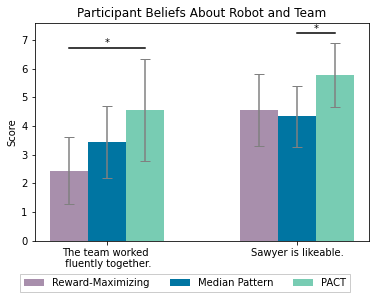

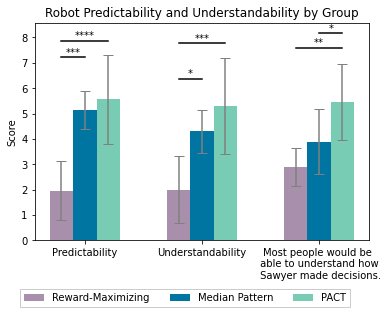

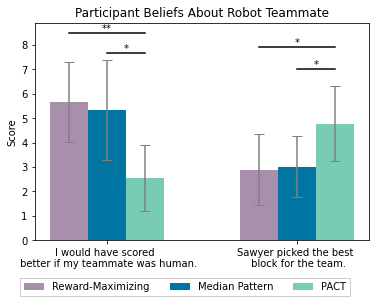

In short, PACT works! But there’s more to it than that. Our results showed that the use of any pattern improved team performance on the coordination task. However! The pattern participants saw mattered, and it mattered a lot. Even though participants in the Median Pattern group played several relatively successful rounds of the coordination game, they didn’t like the robot as much as the participants who saw a PACT pattern. These participants didn’t think the robot was a good teammate, and didn’t feel like most people would be able to understand how the robot made decisions.

Participants felt this way because of the uniqueness of the patterns in the Median Pattern group.These participants could play almost all of the first round coordinating perfectly, while following a pattern different from the robot’s true pattern! After the first round, these participants were certain that they had solved it. When their expectations and assumptions were not met by the robot, their confidence plummeted, as did their feelings about the robot. They never recovered from the mismatch in expectations!

PACT patterns led to fewer mistakes and higher scores for teams. Humans who saw PACT patterns liked the robot, found it both predictable and understandable, and didn’t feel as though a human teammate would have led to a better outcome - which is pretty crazy when you think about it!

Additionally, our interviews uncovered some strange and interesting things! In the optimal group, half of the participants felt the robot behaved randomly, while the other half believed that the robot was following a pattern based on the features they could see. Some were able to articulate complex patterns they felt they saw the robot performing, and many were convinced that with a few more rounds of gameplay they would be able to figure it out. Very few participants in this group felt that the robot knew things about the game that they didn’t. They didn’t think the robot was making decisions based on things they couldn’t see. Even though the robot’s behavior didn’t make sense, only a few people felt that the robot had different information from them.

Curiously, despite many having played perfectly coordinated rounds with the robot, and the entire group achieving over 80% accuracy on identifying the first and last blocks the robot would select in a novel environment, PACT participants struggled to articulate the robot’s decision making process. They found the robot predictable, understandable, and could abstract its behavior to novel environments with ease but less than 17% of them could accurately describe the pattern they saw! Many participants said things like “Something with blue” or “The robot liked blue blocks”. So the robot, while being super predictable, wasn’t explainable at all!

There are some really interesting ramifications for human-robot teaming here. In this case, we do not attempt to balance predictability with optimality (stay tuned for future work where we explore this balance!). Here we show that by matching human expectations based on cognitive science and the human propensity for patterns, we can get better outcomes in a teaming setting - even if we totally ignore optimality. We also found some kooky stuff in our interviews with participants. Participants found the PACT patterns understandable, but couldn’t explain them at all - which raises some interesting questions. Do humans need to be able to explain or articulate robot behavior at all for it to be highly effective? After all, are we really all that good at explaining human behavior either?